The Good News and the Jingshen Kongxu, the Spiritual Void

In his Lectures on Aesthetics (delivered from 1818-1829), the philosopher Georg Hegel identifies a fundamental aspect of the human condition as the tension between spirit and matter: “Spiritual culture produces this opposition in man which makes him an amphibious animal, because he now has to live in two worlds which [often] contradict one another.” It seems evident that in our time the material and the spiritual, the body and soul, are not only interdependent but also in significant tension with one another

Developing at a dizzying pace since its opening up by Deng Xiaoping in the wake of the Cultural Revolution and Chairman Mao’s death in in 1976, China is arguably the economic, political, and increasingly, the artistic powerhouse of our time and the foreseeable future. But beyond these self-evident realities there are more specific reasons for wanting to engage this ancient yet new culture, including startling similarities in the Zeitgeist that can be observed in both China and the West.

Since the opening of China under Deng Xiaoping the Chinese people were given a remarkable level of discretion in the way they lived their personal lives, freedom to travel, all manner of “opportunity” and an economic system that would provide them with greater material wealth and comforts. However, China’s prosperity today has come at a cost.

In 2014 Evan Osnos, long-time Beijing correspondent for The New Yorker, published a book titled Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China. In the last section on “Faith,” Osnos described what I had heard many Chinese friends express to me in fragmented bits and pieces, with varying degrees of clarity and comprehension because their articulation came primarily from lived experience instead of objective analysis. He summarized it like this:

Mao’s Cultural Revolution destroyed China’s old belief system, but Deng’s economic revolution could not rebuild it. The relentless pursuit of fortune had relieved the deprivation in China’s past, but it had failed to define the ultimate purpose of the nation and the individual. The truth now lay in plain view: The Communist Party presided over a land of untamed capitalism, graft, and rampant inequality. In sprinting ahead, China had bounded past whatever barriers once held back the forces of corruption and moral disregard. There was a hole in Chinese life that people named the jingshen kongxu—“the spiritual void”—and something was going to fill it. (p.278-79)

What Osnos described was a crisis of values and meaningful life that the Chinese people are facing in increasingly large numbers.

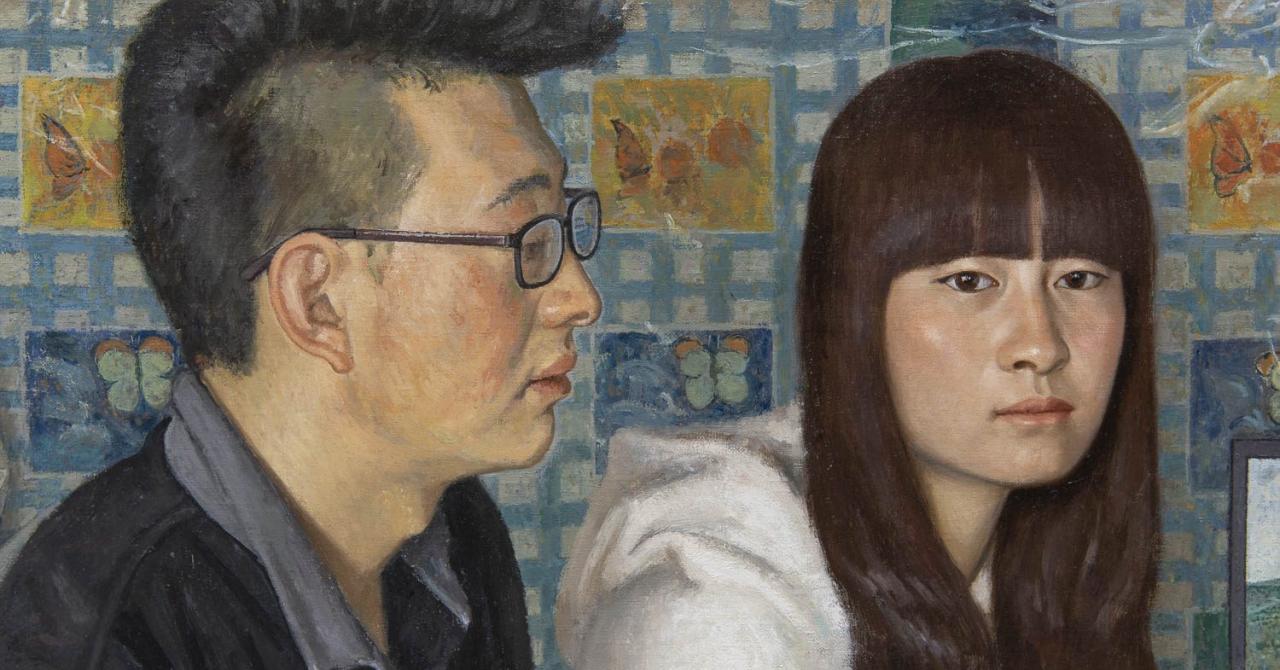

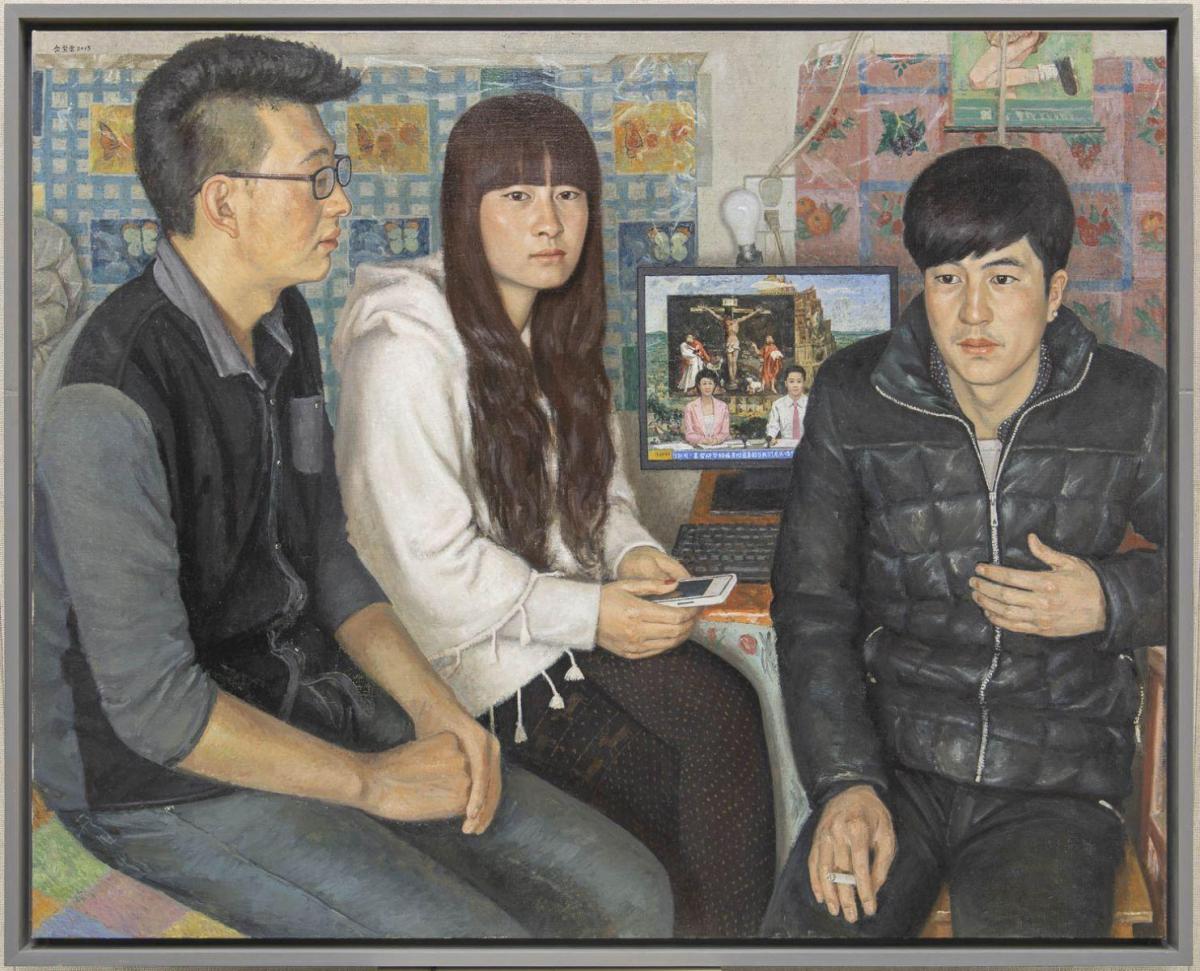

Tong Ziyun’s painting titled News takes up this theme of people suffering from that very human malady—the jingshen kongxu or spiritual void—and their effort to fill it. This painting and his description of it convey stories shared by countless people in China and around the world who find themselves adrift in a material world.

Interestingly, Tong originally titled this painting News Broadcasting: Does Christ’s Suffering Really Have Nothing to Do with Us? The artist explains:

This scene takes place in a home in a poverty-stricken area in northwestern China. During the Chinese Spring Festival holiday, family members return from all over China to their hometowns to celebrate the festival together. The figures in the middle and to the right are sister and brother. They both quit school long before and became migrant workers at ordinary jobs in the city. To the left is their neighbor, a university student studying in the city. These three can stand in for nearly all the young people in rural China: away from their hometown either for university study or for jobs. By any means they have to leave their homes behind to go to the cities so that they may have a chance in life, however slim that chance might be.

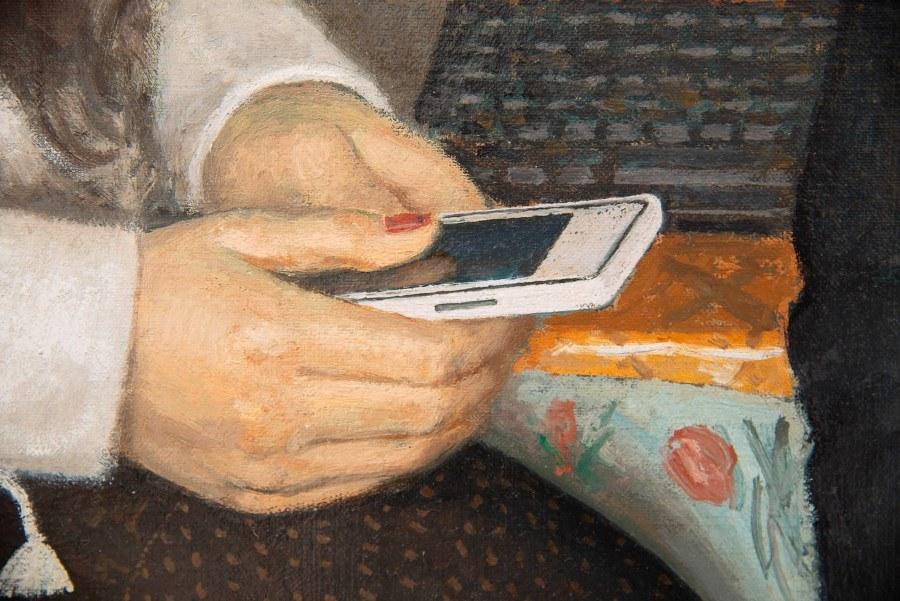

While I was sketching these young people, I chatted with them about Christ and the story of the gospel. From the start they appeared not to understand and to be indifferent, as if it were something that had nothing to do with them, something a million miles away. So I decided to fabricate a series of images on the computer in the painting. I made up a news broadcast by CCTV (the state news-broadcasting station of the Chinese government) titled “Does Christ’s Suffering Really Have Nothing to Do with Us?” On the news-broadcasting screen I appropriated Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Tower of Babel (c. 1563) and Matthias Grünewald’s Crucifixion from the Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-16) in order to reveal a reality.

Significantly, none of this is exclusive to China or to the Chinese people. It is seen in the driving consumerism of developed and developing societies alike that empties people of real purpose and a sense of genuine worth and fills them with the counterfeit currency of material prosperity and the promise of a life focused on pleasures that are fleeting at best.

As Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn observed in his lecture accepting the 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature:

A work of art bears within itself its own confirmation: concepts which are manufactured out of whole cloth or overstrained will not stand up to being tested in images, will somehow fall apart and turn out to be sickly and pallid and convincing to no one. Works steeped in truth and presenting it to us vividly alive will take hold of us, will attract us to themselves with great power—and no one, ever, even in a later age will presume to negate them.

Tong Zinyun’s painting is a poignant illustration of this claim. Juxtaposed with our increasing reliance on technological advances and social media to provide well-being and connection today, the timeless truths represented by the story of the building of the tower of Babel and the Crucifixion of Christ are indeed Good News. Solzhenitsyn was right: when the human capacity to recognize truth and choose genuine good is all but lost, “the whimsical, unpredictable, unexpected branches” of art may yet reveal what is true and what is good to those who have “eyes to see and ears to hear”, as scripture repeatedly tells us.

***

This article first appeared as an ArtWay Visual Meditation 30 May 2021 www.artway.euas Tong Ziyun: News. Posted with permission of the author.

Tong Ziyun 仝紫云, News, 80x100cm, oil on canvas, 2015, with details. Used with permission.

Tong Ziyun’s work discussed in this essay is included in Matter + Spirit: A Chinese/American Exhibition which is composed of 55 works (including some multi-piece, electronic, and serial works) by 25 Chinese and American artists in a wide range of media and styles. The exhibition is traveling across the US through 2023 and can currently be viewed online at The Ridley-Tree Museum of Art at Westmont College https://www.westmont.edu/museum/matter-spirit . For more information about the exhibition and available bookings, contact curator Rachel Smith at rcsmith@taylor.edu .